James Weldon Johnson was born on June 17, 1871 in Jacksonville Florida. Johnson was a writer, educator, and lawyer who was a leading figure during the Harlem Renaissance. While Johnson wrote books such as God’s Trombones, Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson and The Autobiography of An Ex-Colored Man, he is most known as the lyricist of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” now known as the Black National Anthem. After graduating from Atlanta University, Johnson became a teacher and principal of African American students in Jacksonville, Florida. He eventually was the first post-Reconstruction African American admitted to the Florida Bar in 1897. He would eventually return to education at Fisk University and later become the first African American professor at New York University.

In 1901, Johnson moved to New York with his brother, J. Rosamond Johnson and composed over 200 Broadway songs. Johnson moved around and even lived in Venezuela and Nicaragua as a United States consul. During his time as a consul, he wrote some of his published works, like the anonymously published, The Autobiography of An Ex-Colored Man (1912). Johnson joined the NAACP in 1916, becoming the executive secretary in 1920. He remained as the NAACP leader for ten years before leaving to teach creative writing at Fisk University. Johnson died in a car crash in 1938 at the age of 61.

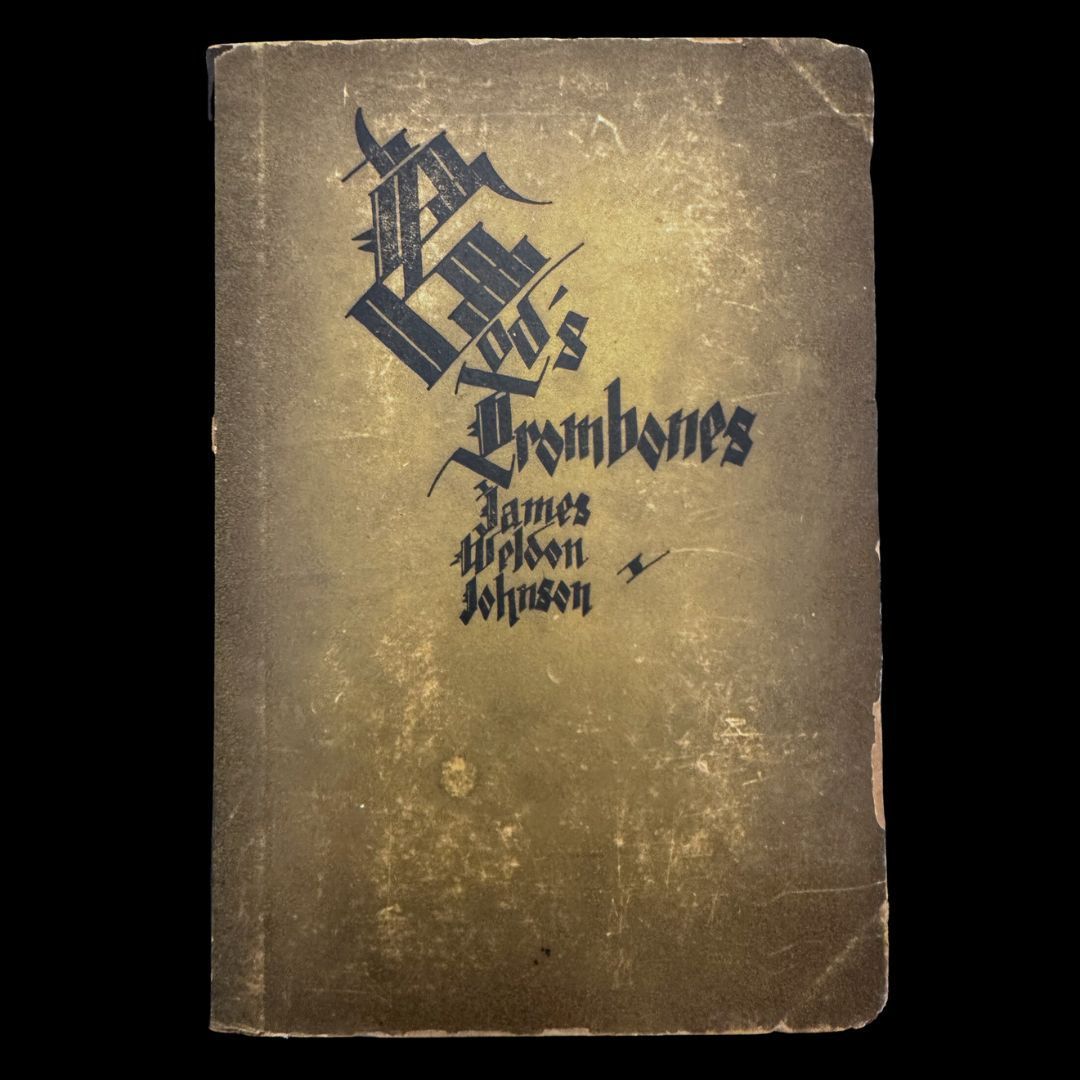

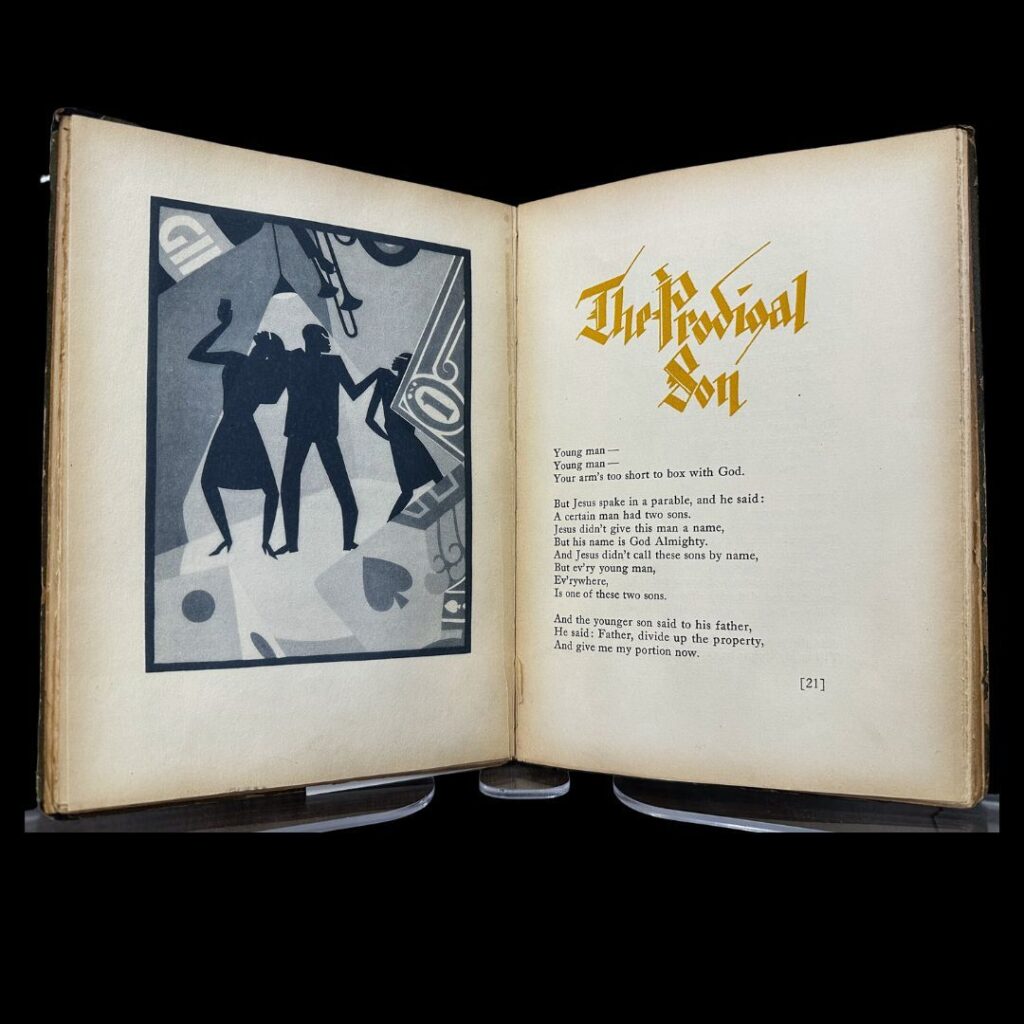

God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse is a book of biblical inspired poems published in 1927. Johnson creates a connection between preaching, jazz music and poetry within his book. In the introduction to God’s Trombones, Johnson tells of a preacher who gave a sermon in the pulpit that matched a performance and his voice acted as a trombone or instrument for his sermon. He describes the voice of the preacher as “not of an organ or a trumpet, but rather of a trombone, the instrument possessing above all others the power to express the wide and varied range of emotions encompassed by the human voice” (p. 7). He goes on to say that the preacher blared, crashed, intoned, moaned, pleaded, and thundered. The sermon moved him so deeply that he wrote ideas for the poem “The Creation.” His captivation with the sermon, to the point of poetic inspiration, is the same reaction of poets like Langston Hughes to jazz music.

The trombone is considered a background instrument in jazz compared to that of the piano, trumpet, and saxophone, so it is curious that Johnson names the trombone the instrument of God. The most reasonable explanation comes from a 2001 New York Times article by Brent Hayes Edwards about jazz called “ Music; An Essential Element in the Voice of Jazz” which describes trombonists as the “paradigmatic second-tier horn man, content to remain out of the limelight” (New York Times). Edwards references James Weldon Johnson’s God’s Trombones and Johnson’s belief that a preacher’s voice matched the sound of a trombone.

By evoking the image of a Black preacher and jazz music, he forges a link between the everyday black life of a church service and a moving performance encompassing the emotions of the congregation. He ends the section by revealing that Spirituals influence his poetry. Langston Hughes, the originator of jazz poetry said something similar in his essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” Hughes alludes to the connection between spirituals and jazz music in everyday Black life, saying “These common people are not afraid of spirituals, as for a long time their more intellectual brethren were, and jazz is their child.”

The Harlem Renaissance, located in Harlem, NYC, was a movement that took place from the late 1910s to the 1930s. The movement was also considered the New Negro Movement at the time, after Alain Locke’s, The New Negro. Some of the leading figures of the movement include W.E.B Du Bois, Arturo Schomburg, Alain Locke, Marcus Garvey. Some of the prominent writers and artists include Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, Jessie Redmon Fauset, James Weldon Johnson, Aaron Douglas and Augusta Savage. At the beginning of the renaissance, few Black people lived in the neighborhood, but by the 1930s, the African American population increased to 70 percent. Part of the reason for the population growth was the Great Migration where Black people in southern states moved North. Because of Harlem’s strong movement filled with some of the best writers, thinkers and artists, many people chose the location as the place to settle. The revival of Black culture, arts, and identity set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.

Though jazz originated in New Orleans, Louisiana, the music genre’s influence reaches all over the globe. Jazz emerged in the late 19th century or early 20th century. It began in the New Orleans African American community. Drawing similarities to blues and ragtime music, jazz also known as “bebop” became a popular form of music right after the Harlem Renaissance. Popular jazz musicians like Dizzy Gillespie and Duke Ellington were regulars at nightclubs in Harlem. The relationship between poetry and jazz took form when poets such as Langston Hughes, the creator of jazz poetry, incorporated the music genre into his work on Black life in Harlem. In his essay, ‘The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” Hughes had this to say about his experimentation with jazz poetry:

“Most of my own poems are racial in theme and treatment, derived from the life I know. In many of them I try to grasp and hold some of the meanings and rhythms of jazz.”

“But jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America: the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile.”

The literary genre of jazz poetry began as an appreciation of jazz. While jazz poetry became notable during the Harlem Renaissance, it was also used during the Beat movement, and the Black Arts Movement. Beside Langston Hughes, Sterling Brown, and Amiri Baraka, jazz poets include Jack Kerouac and Mina Loy as well as Yusef Komunyaaka, Sonia Sanchez, and Michael S. Harper. Some of the most well-known jazz musicians like Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith, Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, John Coltrane, and Miles Davis are all popular figures to use in jazz poetry. One of the most popular jazz poems is “The Weary Blues” by Langston Hughes. Hughes would also name his first book of poems, The Weary Blues.

The relationship between jazz and poetry is so interlaced that April is not only National Poetry Month, but Jazz Appreciation Month (JAM). The history of Jazz Appreciation Month dates back to 2001 when the Smithsonian National Museum of American History decided to recognize the music genre and the April birthdays of many jazz musicians. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) designated April 30 International Jazz Day in November 2011. The Academy of American Poets started National Poetry Month in 1996. What makes a poem jazz poetry is the poet capturing the sound and rhythms of jazz music as opposed to referring to jazz or jazz musicians in a poem.